Dr Kim O’Brien and Dr Brian O’Brien, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Cork

University Hospital, recount the life of

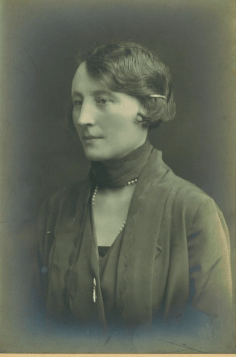

Dr Sarah O’Malley, who was a pioneer of anaesthesiology in Ireland

Sarah (commonly referred to as ‘Sal’) O’Malley (née Joyce) was born in 1896 to a sheep-rearing family in remote Connemara in the west of Ireland and she attended school in Kiltimagh, Co Mayo. This village is the likely etymological root of the word ‘culchie’.

Her family held a progressive attitude towards education. Notably, they taught their children at home, at times employing a private tutor to supplement school lessons. From this background, she entered medical school at University College Galway (UCG) in 1916, graduating as MB, BCh, BAO in 1923. This was somewhat unusual for a woman during this era. Indeed, according to her daughter’s record of events, “nine girls registered for medicine, four of them qualified”. There were apparently approximately 100 medical students enrolled in UCG at the time.

University

Her undergraduate career needs to be put into an historical context, however. While medical education is typically considered demanding in itself, these were years of unprecedented change, division and turmoil in Ireland, as well as globally.

She entered university in 1916, the year of the Easter Rising and the chaotic armed insurrection that much later culminated in the establishment of the Irish Republic, while in Europe, the Battle of the Somme was underway.

During her undergraduate years, the Irish War of Independence took place, a bloody guerrilla war, which typically divided communities, parishes and even families. She was required to take a year out of university to nurse her own family members, most of whom contracted influenza in the great pandemic of 1919.

In fact, her brother Patrick died of the disease in March of that year, while her father died a little while earlier. By the time she was completing university, the country was engaged in civil war. Ireland at that time was a poor country, and in hospitals patients often slept on floors due to very high levels of bed occupancy and demand. The hospitals themselves were largely former workhouses. Perhaps then her strength was already evident by the time she started her professional career.

London

She was now a citizen of the newly-formed Irish Free State, which, as its name implies, had a complicated relationship with the United Kingdom, including tariffs and trade wars. Nonetheless, having worked for a year as a house surgeon in Galway in 1924, and finding herself interested in anaesthesia, the young Dr Joyce moved to London to gain specialist training in the area. This was necessary, since there was no dedicated anaesthesia practitioner in the West of Ireland at that time, and arguably none in the country, since general practitioners and surgeons generally provided such care, albeit in a poorly co-ordinated manner.

Spending several years in London, she studied at a variety of centres, including University College Hospital, Charing Cross, Queen Mary’s and the Chelsea Hospital for Women. Unfortunately, there is very little documentation regarding where precisely she worked during this time, but what is clear is that her training prepared Sal to apply for the post of ‘Visiting Anaesthetist’, advertised in 1929 in the Central Hospital, Galway.

Innovative

This innovative and progressive post was advertised as part-time, and pensionable, with a salary of £100 annually. Suitable applicants, defined as qualified medical practitioners, would ideally have undergone special training in “the modern methods of anaesthesia”. As sole practitioner for such a large area, however, the actual requirements were very onerous. It was mandated that they not only attend the hospital daily at 10.30am, but also at such other times as the “medical staff may require”.

The letter of offer that Sal received is remarkably ungracious and lacking in tones of congratulation — dated 4 October 1929, it reads: “I am directed to state that as no suitable applicant with a competent knowledge of Irish was forthcoming”, she was, by government order, appointed to the position. Ideologically-driven endeavours to re-establish and support the Irish language were intense at this time, with rather limited success. Sal had already worked for a brief time on the Irish-speaking Aran Islands, so she evidently had a good working knowledge of the language, although was not an authentic Gaeilgeoir.

Marriage

By now 33 years old, she was Dr Sarah Joyce-O’Malley, having married Conor O’Malley, an ophthalmic surgeon and Professor of Ophthalmology, approximately five years earlier. He, too, was a remarkable man in many respects and had served in the Royal Navy Medical Corps. He was instrumental in establishing the Order of Malta Ambulance service in Connacht, for which he was later made a Knight of Malta in recognition of his work. He was appointed Professor of Ophthalmology at the Regional Hospital Galway (later known as University College Hospital Galway) after studying cataract surgery with the renowned Dr Mathra Das Pahwa in India after World War I.

Sal and Conor worked together extensively, as she was the only trained anaesthesia provider in the locality for many years, and they had a family of five children. In 1932, she was one of the first to join the United Kingdom Association of Anaesthetists, founded by Dr HW Featherstone, and was invited to take the role of Irish lead for the specialty. This she declined, due to the challenging logistics of travel at the time and her significant family commitments.

Professional respect and success were clearly evident. However, presumably unknown to most of her colleagues, Sal had been forced to engage in a protracted dispute with the county manager in order to receive reasonable remuneration. Having been initially employed on a stipend of £100 annually, she wrote to them in 1945 to emphasise that her salary hadn’t changed in the intervening 16 years.

Clearly this period, encompassing World War II, was a time of major economic turmoil, with inflation of over 5 per cent in Ireland during 1940 alone, for example. In her correspondence she, quite rationally, correlates her salary to that of her surgical colleagues, which had apparently increased significantly in the relevant period, and also offers an overview of her clinical work in defence of her argument.

She notes that her holiday locums are at times paid more than £6 per week — over three times as much as she received. In a lengthy correspondence, she also clarifies the changes she has implemented establishing ‘Safety First Principles’ and by providing structured tutorials to House Surgeons in an effort to reduce operative risks, with the latter changing post every three months. Finally, by the middle of the 1950s, her remuneration was set at just over £800, perhaps giving a proportionate acknowledgement to the exceptional service she pioneered and delivered.

‘Superlative standard’

Dr Joyce-O’Malley was obliged to maintain this correspondence about payment for over 13 years, and at times it offers an insight into her clinical performance. Writing in 1945, she records that she takes “pride in the fact that during my 16 years dealing with very many thousands of anaesthetics, I did not have a single fatality”, while observing that two deaths arose during those years when anaesthesia was administered by House Surgeons.

In another letter, she cites a record of having provided care during more than 4,500 tonsillectomy cases without a single mortality. One can compare this to the outcomes contemporaneously described by Beecher of about one fatality per 1,500 anaesthetics; her claim is thus credible, while also impressive.

Given her professional isolation, the basic technology of the era, the drugs in use, and the limited monitoring available, her clinical performance appears to have been of a superlative standard. Of Sal’s professional reputation, her daughter wrote that “her coolness in a crisis was remarkable and it was on such occasions that her true expertise so frequently averted a tragedy”.

Sadly, most of the evidence relating to the contributions Sal made to teaching and training is only documented in these letters to the county manager, while the rest is anecdotal. It is widely accepted that both she and her husband were popular and leading medical practitioners and educators, rated highly by patients and colleagues. She undertook what we nowadays call a clinical audit; however, there are no formal publications of her work or research, which was largely clinical and reflective of the era.

While still in service of the hospital, Dr Joyce-O’Malley died quite suddenly at the relatively young age of 62. The cause of her death remains unclear.

Legacy

There are three major ways in which Dr Joyce-O’Malley’s legacy is evident today. In the 1940s, in Ireland, the gender pay gap was over 40 per cent and it appears that all of her surgical colleagues were male. Her personal campaign probably helped to address such inequitable arrangements. Secondly, her courage in undertaking advanced training in England in the immediate aftermath of the War of Independence, and of consolidating links to the United Kingdom Association of Anaesthetists thereafter, was quite likely the start of the warm professional relationship that remains today between Ireland and the UK, across borders that once again seem contentious.

And finally, of course, there are many people alive and well as a result of her excellent care, whether they themselves or their parents were cared for by her. Several of her children and grandchildren also trained in medicine and surgery, some of whom are still in practice. The National University of Ireland, Galway, annually awards The O’Malley Gold Medal to an outstanding undergraduate, an award named in recognition of the careers of both Sarah and Conor O’Malley.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Valerie Nestor of Galway, Ronnie O’Gorman of the Galway Advertiser, Prof George Shorten and Dr John Cahill of Cork for information, context and advice in the preparation of this article.

This is an edited version of an article published on the College of Anaesthesiologists of Ireland website