A comprehensive overview of the pathophysiology, presentation, classification and management of psoriasis

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated skin condition which affects approximately 1-to-3 per cent of the population. The Burden of Psoriasis Report estimated that there are 73,000 patients with the skin condition psoriasis in Ireland, suggesting a prevalence of 2 per cent and at least 9,000 patients living with severe disease.

In 2014, the World Health Organisation (WHO) recognised psoriasis as a serious non-communicable disease (NCD) in the World Health Assembly resolution WHA67.9. The resolution highlighted that many people in the world suffer needlessly from psoriasis due to incorrect or delayed diagnosis, inadequate treatment options and insufficient access to care, and because of social stigmatisation.

Clinical presentation of psoriasis

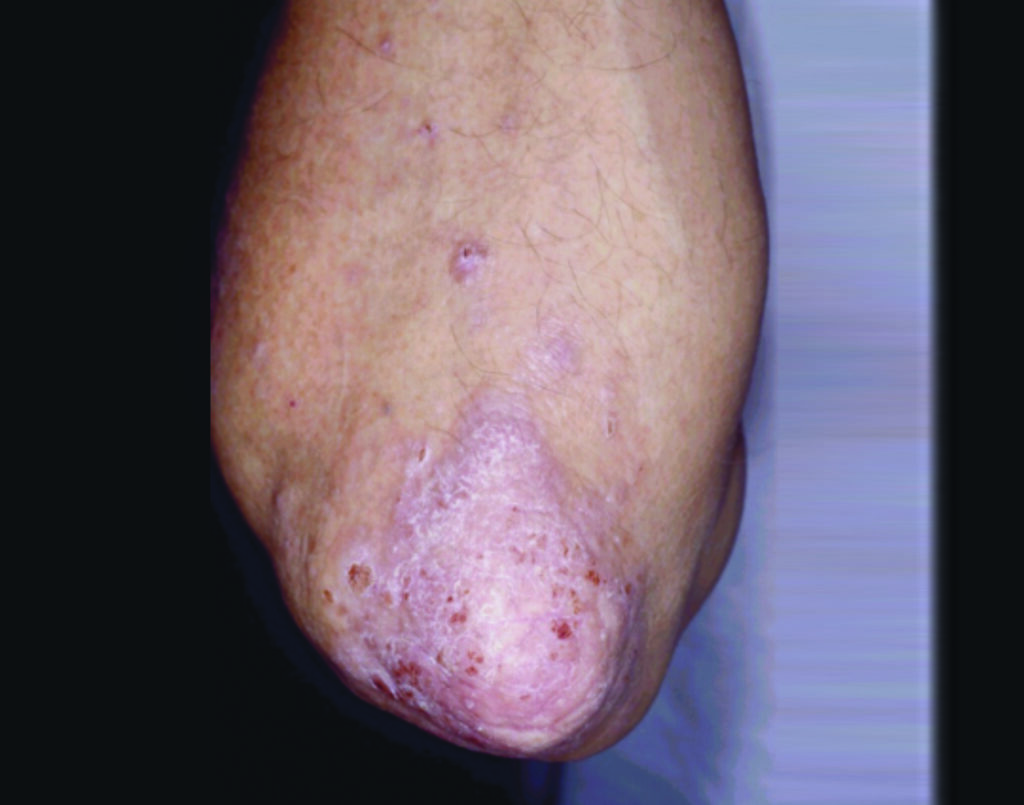

The most common form of psoriasis (Psoriasis Vulgaris) is characterised by scaly, erythematous plaques which affect the extensor surfaces and scalp in a symmetrical fashion, but lesions can affect all parts of the body (Figure 1.1). Typical psoriasis vulgaris is usually early onset, before 35 years of age, with genetic predisposition, and environmental triggers such as streptococcus predominate.

Psoriasis may also present later in life or may be induced by certain medications such as lithium and beta-blockers. Guttate psoriasis is a subtype precipitated by a streptococcal throat infection and presents as small plaques over the trunk and limbs. Palmoplantar pustular psoriasis affects the palms and soles of the feet, with hyperkeratosis, pustules and inflammation.

Nail psoriasis

Approximately 50 per cent of patients with psoriasis will have nail psoriasis consisting of pitting, ridging, onycholysis and ‘oil spot’ and nail dystrophy. It is common, because of the destruction of the nail plate, for patients to have intercurrent fungal infections.

Psoriatic arthritis

Up to 40 per cent of patients may develop psoriatic arthritis, usually after the onset of skin disease. Psoriatic arthritis is an erosive seronegative (rheumatoid factor negative) arthritis which may present in five distinct phenotypes as elucidated by Moll and Wright. This may be a peripheral arthritis, spondylitis, enthesitis (inflammation of tendon insertions) and dactylitis. Because of the development of erosion, it is important to detect psoriatic arthritis as soon as possible to prevent debility.

Psoriasis pathogenesis: Genetic predisposition

The pathogenesis of psoriasis integrates environmental triggers on a genetic background. The heritability of psoriasis is complex and twin studies have shown that monozygotic twins are 65-to-72 per cent more likely to have psoriasis compared to 30 per cent for dizygotic twins.

A population-based study found that 36 per cent of probands had a parent with psoriasis. The relative lifetime risk of getting psoriasis if no parent, one parent or both parents have psoriasis is 0.04, 0.28 and 0.65, respectively

Recent Genome-wide association scans have found almost 40 susceptibility loci have been subsequently identified in psoriasis linked to adaptive and innate immunity.

Environmental triggers: Infection

The onset of psoriasis after a streptococcal sore throat was noted in the 1950s. Subsequent work in the 1970s found that lymphocytes from patients with psoriasis, particularly guttate psoriasis showed heightened responses to streptococcal A antigens. Psoriatic lesional skin demonstrated strong cross-reactivity with monoclonal antibodies reactive to Group A streptococci compared to sera, normal or un-involved psoriatic skin.

This led to the hypothesis that proteins in psoriasis skin which shared common epitopes to streptococcus antigens resulted in inflammation in the skin during a streptococcus infection.

Psoriasis is also induced by HIV, onset of psoriasis in some instances may be the presenting symptom of AIDS. HIV-associated psoriasis tends to be refractory and reports exist of the use of all traditional treatment modalities, but scant formal trials. Highly-active antiretroviral therapies appear effective in treating psoriasis in patients with HIV.

Environmental triggers: Stress

In 1977, Seville RH reported a follow-up of 132 psoriasis patients cleared with dithranol over a three-year period. Around half (51 per cent) of patients reported a specific stress before recurrence of psoriasis. Another study which looked at different dermatological conditions such as psoriasis, urticaria, and atopy, confirmed that in certain patients with psoriasis a stressful life event such as bereavement predated the onset of psoriasis. In a large case-control study of Italian patients with psoriasis, Naldi found stressful life events to be a significant trigger for a first episode of guttate psoriasis.

An endocrine explanation for exacerbation of psoriasis by stress was suggested by Arnetz et al. This group reported that psoriasis patients when stressed had higher levels of urinary catecholamines and lower levels of plasma cortisol. Later work found that during periods when psoriasis was active, serum cortisol levels were raised and serum adrenaline levels were depleted. This was associated with lower levels of immunoglobulins and altered complement levels. Several studies have shown that psoriasis patients are chronically hypocortisolaemic and mount attenuated stress responses.

Environmental triggers: Drugs

Psoriasis may be initiated (drug-induced) or exacerbated (drug-triggered) by certain drugs such as lithium, anti-malarials, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and terbinafine. Lithium has been described as both inducing psoriasis and exacerbating psoriasis since the 1970s.

In the 1970s reports began to appear in the literature of psoriasiform eruptions induced by early beta-blockers such as practolol and oxprenolol.

This was followed by reports of propranolol, metoprolol and atenolol inducing and exacerbating psoriasis. In a large population-based controls study using the UK GP research database, no association was found between the use of beta-blockers and psoriasis, however.

The induction of psoriasis by synthetic anti-malarials became apparent in the 1960s when these agents were used as disease-modifying agents in psoriatic arthritis. A systematic review of the literature in 1999 could not find strong evidence of anti-malarials inducing psoriasis, however.

Corticosteroids when first introduced appeared to offer benefit to patients with psoriasis, but it quickly became apparent that withdrawal of oral or potent topical corticosteroids could result in exacerbation of psoriasis. Other medications implicated in the induction of psoriasis include angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, while as mentioned NSAIDs have also been associated with induction of psoriasis, which is problematic as these agents are widely used to control joint pain in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Despite these reports, in practice psoriasis is influenced uncommonly by concomitant medication.

Environmental triggers: Smoking

Several researchers have suggested that smoking may be a risk factor for the development of psoriasis. In a case control study of 108 patients, Mills demonstrated that patients showed a significant association with smoking prior to onset of psoriasis (OR=5.3). In a case control study of Italian patients, Naldi found that the risk for the development of psoriasis was higher in ex-smokers and current smokers than in patients who had never smoked.

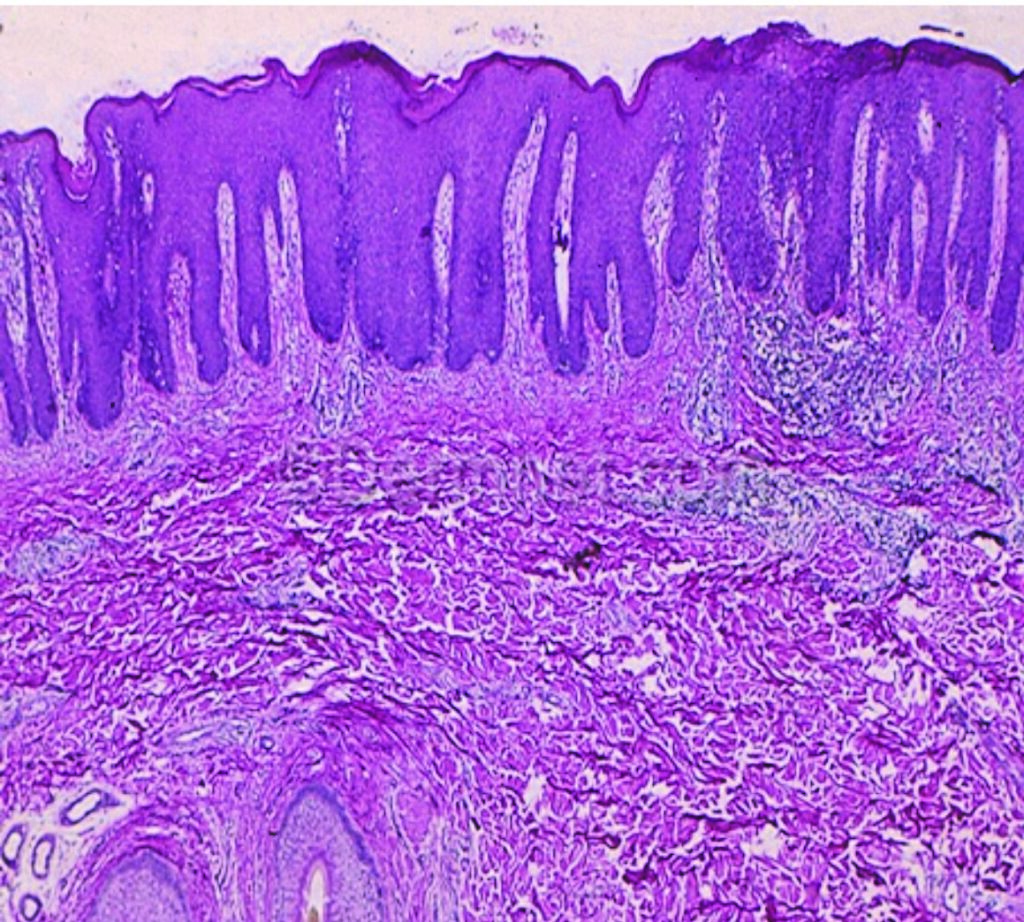

thickened epidermis with elongation of the rete pegs (A)

In a review of the published studies on smoking, Behnam controlled for alcohol and reported that women who are smokers have a 3.3-fold increased risk of developing plaque psoriasis.

Smoking also appears to adversely affect the natural history of psoriasis. In a hospital-based cross-sectional study of Italian patients admitted to hospital for treatment of psoriasis, smoking more than 20 cigarettes a day confers a two-fold higher risk of clinically more severe psoriasis. Behnam’s review found both sexes who were smokers had reduced improvement rates.

Environmental triggers: Alcohol

Patients with psoriasis have higher levels of alcohol consumption compared to the normal population. Drinking large amounts of alcohol predisposes to psoriasis. A mechanism for the exacerbation of psoriasis by ethanol is suggested by work which showed that ethanol stimulates proliferation of cultured keratinocytes.

Psoriasis patients who drink excessive alcohol have more severe psoriasis and higher levels of psychological distress. We have shown previously a higher prevalence and incidence of psoriasis in a population of patients with alcoholic liver disease. There is also a suggestion that alcohol consumption may adversely affect treatment outcomes in patients who continue to consume excess alcohol.

Pathogenesis of psoriasis

Pathogenesis of psoriasis: Keratinocyte hyperproliferation

The pathogenesis of psoriatic plaques in the skin is the result of several phenomena: Hyperproliferation of keratinocytes, an influx of inflammatory cells into lesional skin, and angiogenesis. Keratinocyte maturation is accelerated and gives rise to thickening of the epidermis and the characteristic psoriasiform hyperplasia seen histologically.

The clinical manifestation of this process is thickened plaques on the skin (Figure 1.2). Two distinct defects are apparent, hyperproliferation and altered terminal differentiation of keratinocytes. Most early treatments for psoriasis such as tar, vitamin D analogues and dithranol were based on their anti-proliferative effects.

Pathogenesis of psoriasis: Infiltration of T-helper lymphocytes

Ciclosporin, which had been shown to decrease keratinocyte proliferation, was clinically shown to improve psoriasis. Subsequent research found that ciclosporin treatment decreased T-lymphocytes in skin biopsies of treated patients leading to the first indication that psoriasis was a T-cell mediated disorder.

The efficacy of ciclosporin in psoriasis pointed to the discovery of infiltration of lesional immune cells, namely T-helper lymphocytes as a key feature of the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Treatment with PUVA, dithranol, topical steroids and ciclosporin reduced the dermal infiltrate of T-cells. The initial defect of keratinocyte hyperproliferation appeared to be induced by cytokines from T-cells.

Tissue from guttate psoriasis showed the presence of T-cells reactive to Group A Streptococcus antigen. As alluded to above, activated keratinocytes presented bacterial-derived super antigens to T-lymphocytes. The cytokines released from lesional and non-lesional T-cells in psoriasis produced Th1-lymphocytes cytokines in vitro and later work characterised the infiltrate as producing predominantly Th1-cytokines. The use of anti-TNF alpha therapies such as infliximab in psoriasis and their efficacy re-iterated the centrality of Th1-cells in psoriasis pathogenesis.

Twelve years later Th17 lymphocytes, a novel subset of T-helper lymphocytes, expressing IL-17 were described. Th17-cytokines were found to be over-expressed in psoriatic lesions. As with many other diseases traditionally believed to be caused by Th1-lymphocytes, it is apparent that Th17-lymphocytes are also pathogenic with discrete populations of both lymphocytes present in psoriasis lesions.

Pathomechanisms of psoriasis: Innate immune cells

Although Th1 and Th17 are clearly important in inducing psoriasis lesions, innate immune cells also play a part in the formation of plaques. Innate immune cells capable of producing TNF-α and IFN-γ in psoriasis plaques are NK cells, NK-T-cells, dendritic cells, neutrophils and macrophages which have all been identified in psoriasis lesions.

Comorbidities in psoriasis

Classically considered to be a disease of the skin it is now evident that psoriasis patients suffer significant comorbidities. These include psoriatic arthritis, obesity, premature cardiovascular disease and depression. It is not clear whether these conditions influence psoriasis or whether psoriasis influences these comorbidities. There is emerging evidence that a complex relationship exists between psoriasis and its concurrent associated diseases.

Cardiovascular disease in psoriasis

The increased incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with psoriasis was recognised by McDonald and Calabresi in 1978. They reported that patients with psoriasis had a 2.2 times higher incidence of arterial and venous vascular disease when compared to controls in a clinic-basedcase control study.

Since then most studies have been large retrospective or prospective database studies. The largest prospective study used the UK General Practice Database. Psoriasis appeared to confer an independent risk of myocardial infarction. The investigators controlled for diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, body mass index, age, sex, and smoking. This risk was greater for younger patients with severe psoriasis. A second group utilising the same data found an increased incidence of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, as well as increased rates of myocardial infarction, angina, stroke and peripheral vascular disease.

Retrospective studies from Sweden, Germany, and Finland previously documented increased rates of risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and obesity in patients with psoriasis. Poikolainen and Mallbris reported increased cardiovascular mortality in psoriasis patients who were hospitalised for treatment of their disease. Patients managed as outpatients, however, did not have excess risk, suggesting that more severe disease was associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease.

Psoriasis and obesity

In a case-control study, assessing cardiovascular risk in psoriasis we found patients with psoriasis were more likely to be obese. Increased rates of obesity in psoriasis patients has been documented in cross-sectional studies of large healthcare databases and case-control studies. The incidence of obesity is increased in psoriasis patients but several studies have also found obesity to be a risk factor for the development of psoriasis. Patients with more severe psoriasis were more likely to be obese compared to normal controls in cross-sectional and case-control studies.

Psoriasis and psychological distress

Psoriasis can be psychologically devastating and patients’ lives become especially difficult when psoriasis is present in highly visible areas of the skin such as the face and hands. Related psychological problems can affect every day social activities and work. It causes embarrassment, lack of self-esteem, anxiety and increased prevalence of depression. Patients with psoriasis report experiencing anger or helplessness, and they disclose a higher rate of suicidal ideations than other patients.

Assessment of psoriasis

Psoriasis severity is measured using an objective assessment known as the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). This is a measure that integrates the redness, thickness and scaliness of psoriasis multiplied by the area for the head, trunk, arms and legs. The score runs from 0 to 72, less than 10 is considered mild disease, 10-to-15 moderate disease and greater than 15 severe disease.

In addition to objective measurement of disease severity, the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is used to assess the impact of having psoriasis on patients’ quality-of-life in the domains of symptoms, leisure, work and school, personal relationships and the impact of treatment, and is as follows: 0-to-1 no effect at all on a patient’s life, 2-to-5 being a small effect on the patient’s life, 6-to-10 moderate effect on the patient’s life, and 11-to-20 being a very large effect on the patient’s life, with 21-to-30 an extremely large effect on the patient’s life.

The Physician Global Assessment (PGA) is less commonly used and is rated 0-to-3 as clear, mild, moderate and severe, or Body Surface Area (BSA) whereby the area of a palm of a hand equals 1 per cent. A useful rule of thumb is the rule of 10’s; if PASI >10, or DLQI >10 or area BSA >10 the patient should be referred for assessment by a dermatologist.

Screening for co-morbidities

It is important to check for psoriatic arthritis and a simple question regarding early morning stiffness can ascertain the presence of joint involvement. It is also important to screen for mood disturbance such as depression and anxiety.

Screen for triggers

Assessment should also take into account an individual’s triggers for psoriasis, eg, smoking, excess alcohol consumption, stress and recurrent strep throat infections. Understanding and minimising these triggers can be an important part of the long-term management of psoriasis.

Treatment of psoriasis

Mild psoriasis usually is treated with topical therapy, progressing to phototherapy in the case of insufficient response. Moderate to severe psoriasis requires systemic therapy.

Mild psoriasis

Mild psoriasis may be treated topically with mild-mid potency topical steroids. Potent topical steroids such as clobetasol should not be used on plaque psoriasis on the body, as they may worsen psoriasis on stopping in a phenomenon known as ‘rebound’. Potent topical steroids may be used on palmoplantar and scalp psoriasis. Vitamin D analogues such as calcipotriol alone or in combination with betamethasone (Dovonex and Dovobet) are also indicated for mild to moderate psoriasis.

Tar in combination with salicylic acid acts as a keratolytic and is also anti-inflammatory and may be used on scalp and plaque psoriasis. Facial and genital psoriasis may be treated with topical hydrocortisone or clobetasone (Eumovate), and tacrolimus (Protopic 0.1 per cent) may be used to maintain control in these areas. Ointment forms should be used for preparations and patients should also use a bland daily moisturiser such as Silcock’s base or emulsifying ointment.

Scalp psoriasis needs a descaling agent such as tar/salicylic acid or a vegetable oil (olive oil, coconut oil or almond oil) applied to the scalp and then combing out the scale. Topical steroids may then be applied in the form of scalp application. Tar shampoos may also be useful and if scaly through the scalp an antifungal shampoo may help.

Moderate to severe psoriasis

Phototherapy

Phototherapy is provided in 11 departments of dermatology and a number of peripheral dermatology departments throughout the country. Phototherapy is very useful for patents who get intermittent flare-ups of psoriasis or in patients with guttate psoriasis.

TL-01 UVB treatment requires a patient attending three times a week for up to 10 weeks. PUVA involves producing psoralens in the skin either by bathing or ingesting psoralen and then exposure to UVA and is performed twice weekly. Remission, whereby a patient’s psoriasis clears and does not return for a time from six months to two years, is possible with phototherapy.

Systemic medications

For those patients who fail phototherapy or who have joint involvement, systemic treatment is indicated. Commonly used first-line drugs include methotrexate, fumaric acid esters, acitretin and apremilast. In patients with severe flares of psoriasis, ciclosporin may be used as it has a rapid onset of action, but prolonged use is avoided due to side-effects such as hypertension and renal failure.

Several triggering factors have been identified leading to the first manifestation of psoriasis or flares of a stable chronic disease. Understanding and minimising these triggers can be an important part of managing psoriasis.

Biological medications

The treatment of psoriasis has been revolutionised by the introduction of new biological therapies and more than any other skin condition, the treatment armamentarium for patients with psoriasis has expanded significantly. It is not unrealistic to proffer clear skin to many patients who have lived with this stigmatising condition all their lives.

Anti–TNF therapy

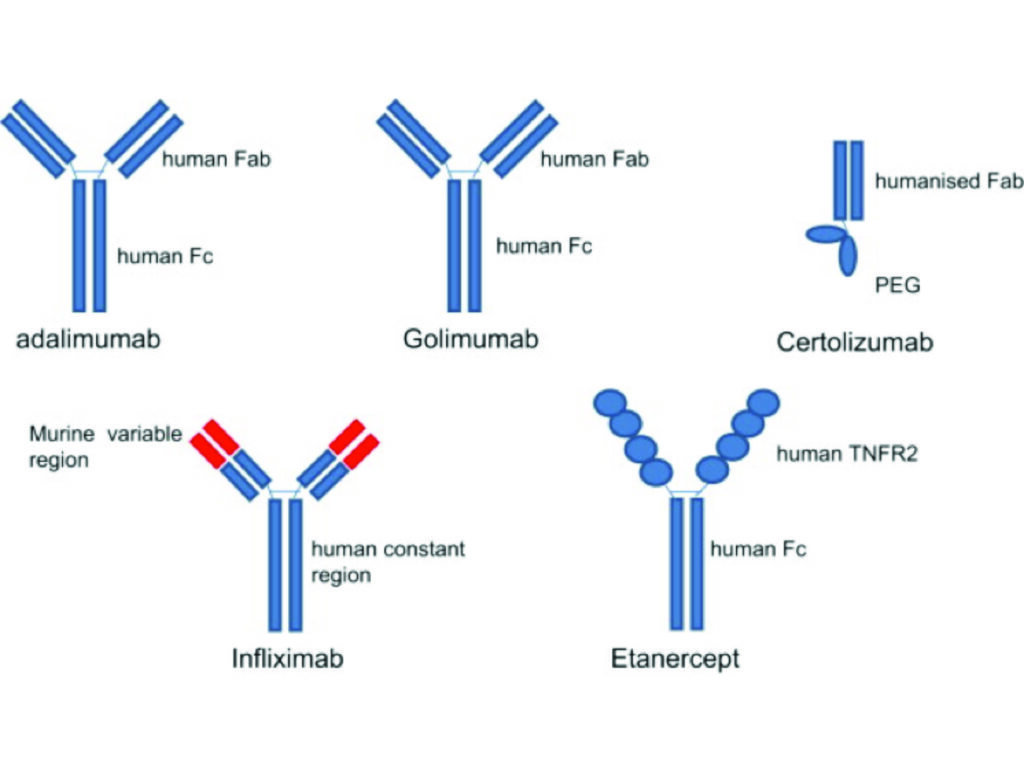

Etanercept subcutaneously was approved for the treatment of psoriasis by the US FDA in 2004, followed by infliximab intravenously in 2006 and adalimumab subcutaneously in 2008. Certolizumab is the newest TNF inhibitor to be licensed for the treatment of psoriasis in 2018 and is the only member of this class to be licensed for use during pregnancy; an important consideration in patients of childbearing age.

Psoriasis was the first indication for which ustekinumab was licensed by the FDA in 2009 and paved the way for the development of targeted therapies for psoriasis.

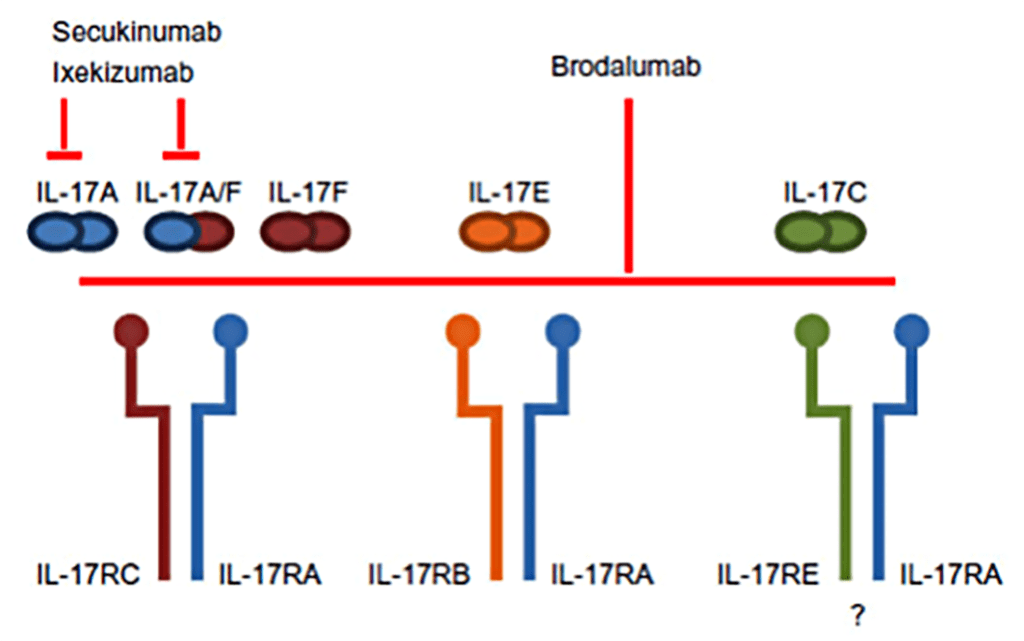

Anti IL-17 therapy

Secukinumab was the first IL-17A inhibitor approved in 2015 for treatment of patients with psoriasis. Ixekizumab, which also targets anti-IL-17A, was licensed the following year in 2016. Brodalumab, which interacts with IL-17RA, is the third member of this class and was licensed in 2017.

With this group of treatments for the first time clear or almost complete clearance of psoriasis was being discussed as an endpoint of clinical trials and an attainable goal for patients.

Anti-IL-23 therapy

Guselkumab, an IL-23p19 neutralising antibody, was approved by the FDA in July 2017. This has been followed by tildrakizumab in 2018, while risankizumab, another antibody targeting the IL-23 pathway, was licensed by the FDA in 2019.

New treatments in the pipeline

Clinical trials are ongoing in the development of new injectable, oral and topical treatments for psoriasis, so patients and clinicians will have a wider choice of treatments. This rapid expansion of treatments for psoriasis has, as stated previously, enhanced our understanding of the disease. Research is also ongoing to identify predictors of treatment response in psoriasis patients.

The UK’s Psoriasis Stratification to Optimise Relevant Therapy (PSORT) consortium aims to better understand the determinants of response of psoriasis to biologic therapies and deliver, in close collaboration with commercial partners, a PSORT stratifier (algorithm) to guide psoriasis management. PSORT will help to: optimise clinical pathways for psoriasis; inform the management of other less accessible immune-mediated inflammatory diseases; and deliver healthcare savings by efficient prescribing of biologics.

Summary

Psoriasis can have a significant impact on patients’ quality-of-life and health which is important not to underestimate. Treatments for psoriasis have advanced such that patients can expect to have clear or nearly clear skin.

References on request