The lack of recognition of medication overuse and medication-overuse headache has resulted in a significant burden for patients

Headache is a very common complaint in primary care, accounting for up to 5 per cent of all general practice consultations. Most patients attending doctors suffer from primary headache disorders, predominantly migraine (more than 90 per cent). Migraine is often treated with painkillers or acute medications. In fact, this is the most common reason for analgesic use in the general population. Many migraine patients unfortunately acquire the additional complication of medication overuse (MO), which can in turn lead to medication-overuse headache (MOH). Migraine patients who have MO and/or MOH are often very debilitated and this group of conditions together are a substantial burden on society.

During our undergraduate training we all received training about the headache that is associated with a potentially sinister or life-threatening secondary headache condition, for example, sub-arachnoid haemorrhage (SAH). GPs see three-to-four people with SAH during their medical lifetime. To date, there was been little emphasis on MO and MOH in the undergraduate medical curriculum, despite the latter being more frequent.

MO, MOH and probable MOH are seen frequently in general practice (and often not diagnosed); 1-to-2 per cent (in developed countries), with a range between 0.5 per cent and 7.2 per cent. The highest prevalence has been shown in Russia (7.2 per cent). The prevalence of MO/MOH in specialist headache clinics in Ireland and internationally ranges from 30-to-50 per cent. ‘Status migrainosus’ is when a debilitating migraine attack lasts longer than 72 hours. It may often be caused by MO.

Medication overuse

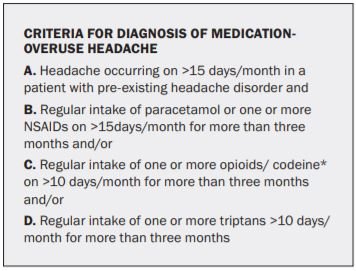

MO is formally defined as the use of:

- Simple analgesia (such as paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs)) 15 or more days per month for at least three months, OR

- Combination analgesics (often codeine/opiate based, such as Solpadine) or triptans 10 or more days a month for at least three months

- It is important to differentiate between the practice of MO (that is, taking painkillers, NSAIDs, triptans or combination products too frequently) and the secondary headache condition, MOH. Determining MO is generally very easy in a cohort of migraine patients as long as a detailed history is taken.

Difficulties encountered in taking a detailed history for MO

In general practice, some patients may be impatient and unwilling to give a detailed history as typically their primary goal is to get ‘quick fix’ for the pain and the other disabling symptoms. In addition, general practice is usually very busy and the standard consultation time is insufficient (10-to-15 minutes). Furthermore, in our clinical experience:

- Some patients are poor historians and are more resistant to history taking and giving exact details of how much medication they are taking;

- Patients with MO (and MOH) are typically more resistant to repeated questioning and may be more defensive;

- Patients do not usually volunteer information on how much acute medication they are taking as they may be trying to hide it;

- Many of them do not understand that it is related to the worsening of their headaches.

Together, these multiple issues often result in an unsatisfactory consultation, and contribute to under-diagnosis and under-treatment of MO, MOH and probable MOH. Therefore, a complete list of all non-prescribed and prescribed medications should be obtained with a view to assessing if the patient has MO or more rarely, MOH in those who have headaches. In clinical practice, we have found that many headache/migraine patients may need to be interviewed several times about their symptoms and medication intake, often on separate occasions. For some patients, this may feel like an interrogation.

However, the healthcare professional has an obligation to ask probing questions in order to do everything possible to get the correct diagnosis, so that they can treat the patient appropriately. The key factor for defining MO is the number of days per month that acute medication is taken for headache. It does not appear to be relevant in this context whether a single dose or multiple doses of the acute headache medication are used on a particular day.

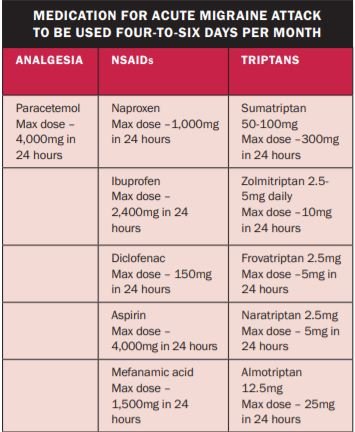

In our clinical practice, we generally advise our headache patients that analgesics or acute medication should be used no more than four-to-six days per month (see Table 1), in order to avoid MO. The overuse of medication typically begins with patients taking over-the-counter (OTC) painkillers more regularly, and this often starts well before the patient consults with their GP. When the practice of MO leads to a change in headache pattern and resistance to conventional migraine prophylactic treatment, the patient is then described as having MOH or probable MOH.

MO – When is it time for prophylactic migraine treatment?

MO in the context of more chronic migraine is a worldwide public health problem. Despite repeated public awareness campaigns nationally and internationally over the last two decades, this issue is still a significant cause of disability in a large proportion of high-frequency episodic and chronic migraine patients. As a general guideline, preventive or prophylactic therapy is indicated in patients with migraine who have headache and associated neurological symptoms:

- On eight-to-10 days per month or more (usually for a period of at least three-to-six months);

- And have at least moderate disability due to their headache attacks. In other words, the key factors in decision making are the number of days per month that patients experience symptoms, together with the level of disability in each individual migraine patient. An additional aim of preventive therapy is to try to treat moderate- and high-frequency episodic migraine effectively before MO develops. It should be emphasised that if there is established MO and chronic migraine, there is strong evidence to suggest that many conventional prophylactic treatments are ineffective or less effective.

A pragmatic individualised approach to preventive therapy needs to be taken with patients who experience intermediate-frequency episodic migraine and associated migraine symptoms between five-to-seven days per month, considering:

- The level of disability from migraine attacks;

- Efficacy of the prophylactic treatment in each specific individual;

- Patient preference; and

- Severity of side-effects to a specific preventative therapy should dictate whether or not a patient starts with (or continues on) prophylactic treatment.

We do not feel that it is appropriate to offer medium-term (typically one-to-two years) conventional daily oral prophylactic medications for migraine to patients with one-to-four migraine or headache days per month. We consider this practice to be somewhat excessive, due to the associated side-effects of daily medications and the lack of overall efficacy of these preventive agents. Patients with low-frequency episodic migraine should be encouraged to treat early with a combination of acute medications.

Strategies for prevention of MO in migraine patients

We recommend an integrated care approach to prevention and management of MO in patients with migraine. This should involve hospital-based healthcare professionals (neurologists, specialist nurses, psychologists, etc), primary care physicians, pharmacists, general practice nurses, community psychology and psychiatry, and the voluntary patient groups, such as the Migraine Association of Ireland (MAI). We feel that the following should be considered to try and prevent MO and MOH:

1) Written patient information leaflets/booklets on MO have been developed and should be given to those migraine patients who are potentially at risk of progressing to MO.

2) Pharmacists are ideally placed in primary care to identify patients who may be at risk of MO. Therefore, it is essential to include and collaborate with pharmacists to highlight this message to patients.

3) The value of pharmacy involvement has now been highlighted through their inclusion in the national Sláintecare headache programme.

4) The MAI also provides written information for patients and has extensive information on their website about MO and MOH.

5) Headache diaries should record which acute medications are used and how frequently. As chronic headaches are assessed over a three-month period, a review of the last three months of the diary is ideal.

6) There should be caution in primary care and emergency departments when prescribing codeine (which is metabolised as an opiate) or opiate-based analgesia, as they are often responsible for MO and there is also the potential for dependence and possibly addiction.

Opiate-based medication may also cause drowsiness, incoordination and possibly impair driving. All patients should be advised of this when they get a prescription. It is generally advised that headache patients should avoid codeine, tramadol, and other opiate derivatives. Most migraine patients with MO will have been in contact with their GP for their headache. In fact, almost half will have had such a contact in the previous year. The GP, therefore, should have a key role in providing education, advice, and support, in addition to prescribing prophylactic medication where appropriate. This would be particularly true for those with a medical card in Ireland, as most (or all) medications are put on the general medical services (GMS) prescription.

Medication-overuse headache

MOH appears to be almost exclusive to those who suffer from migraine. The term was first used in 2004. Historically, since its initial documentation in the 1950s this type of headache has been called analgesic rebound headache, medication misuse headache, transformed migraine or drug induced headache. A three-month headache diary may be useful for patients to keep a detailed record of medication use. The most common medications, most of which have been mentioned previously, are implicated and include:

- Simple analgesia (such as paracetamol);

- Combinations of paracetamol or ibuprofen with codeine (eg, Neurofen plus or Solpadine);

- Paracetamol/tramadol combination;

- Triptans (now that sumatriptan is available OTC);

- Tapentadol and other opiates.

Patients may substitute one for the other. The perfect example being the reduction in use of codeine since the 2007 Irish (and international) campaign to reduce analgesic use and the concomitant increase in the regular use of triptans and simple analgesia. On a national level, people have become aware that analgesia are available more freely in Northern Ireland (or Spain) without a prescription and tend to get a supply when there. Determining MO is generally very easy in a cohort of migraine patients as long as a detailed history is taken. However, diagnosing MOH is a more difficult task.

There is even confusion in the international literature regarding the description and definition of these two related concepts. In recent years, experts speaking on this topic at headache/migraine conferences are usually at pains to define each entity carefully. Management of these patients is also a controversial topic at many of these meetings.

A recent retrospective study from a specialist clinic in Buenos Aires in 2019 documented MO in slightly more than 40 per cent of their chronic migraine patients attending the clinic.

The study also concluded that migraine is the most frequent primary headache, closely followed by the secondary condition MOH. It is important for GPs to consider these problems and identify patients who are overusing acute treatments and also patients with MOH. These individuals are more likely to experience more chronic and disabling headaches which are very difficult to manage unless the diagnosis of MO and MOH is considered and subsequently addressed.

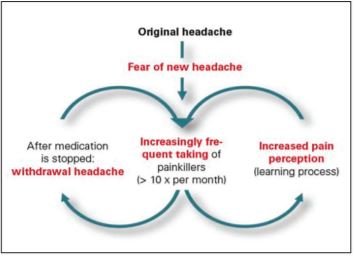

How the cycle of MOH starts

For the sake of clarity, MOH is defined as headache worsening by the practice of MO and is almost always seen in patients with migraine biology. To make the diagnosis of MOH, the headache disorder must become more frequent and chronic. It is recognised as a separate secondary headache disorder in the third and most recent version of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3).

The biological basis of MOH is a topic of international debate and is not clearly understood. In practice, MOH (or probable MOH) develops as a secondary headache disorder following on from MO, in circumstances where the headache frequency increases and this results in increasing acute medication or painkiller use. MOH is then deemed to be clinically evident when there is clear chronification of the headache disorder and concomitant resistance to conventional pharmacological prophylaxis. The overuse behaviour can happen almost without the doctor or the patient realising it is a significant problem.

The diagnosis of MOH is supported if the headache frequency is reduced on withdrawing the offending acute medication. In specific individuals, MOH may be encouraged further as a result of using less effective or non-specific acute medications, resulting in inadequate treatment response and re-dosing. For example, a less effective strategy might be to take paracetamol or ibuprofen alone, rather than a more effective combination approach of paracetamol, ibuprofen and a triptan together at the same time (see Table 1).

*Codeine is metabolised to an opiate

It is very important for GPs, hospital doctors (including physicians in emergency departments), associated healthcare professionals and pharmacists to consider these fundamental problems when seeing or reviewing headache patients. In 2011, a study in Ohio, US, found that excessive use of analgesic post-concussion may contribute to chronic post-traumatic headaches in some adolescents. The neuro-surgical teams in many of our hospitals in Ireland have been advised of this recently. As stated previously, many of these patients’ headaches can usually be managed more effectively once the MO issue has been addressed.

Pharmacists may be the first healthcare professional to recognise patients who have MOH, as already mentioned in relation to MO, as they frequently encounter such individuals in their retail practice. Likewise, individuals with recurrent headaches who have a GMS card often come to the attention of their GP in the first instance due to the repeated requests for analgesia.

Short-term management of MO and MOH

MO and MOH (including probable MOH) have the additional potential for stigmatisation in some patients. It can put pressure on the doctor-patient relationship and blaming the patient should be avoided wherever possible. MOH should not be diagnosed in haste as it is a difficult condition to prove clinically. As outlined previously, a detailed headache and medication history should be taken meticulously, with the aim of detecting a temporal relationship between the practice of MO and the consequent worsening of the primary, usually migraine, headache disorder.

There are a number of different management strategies for dealing with MO and MOH. However, most specialists will provide the following common messages:

Pain at www.change-pain.com

a) Patients need to be counselled that taking acute medication or painkillers regularly may worsen their

headache problem.

b) The aim is to stop all codeine or opiate medication and reduce the number of days that triptans, NSAIDs or simple analgesia are taken (limited to four-to-six days per month, or one-to-two days each week).

c) Withdrawal or significant reduction of the offending medication is usually the first step.

d) In the short- to medium-term, this may result in an increase in headache and associated neurological symptoms and there is the additional possibility of other withdrawal symptoms.

e) Abrupt withdrawal (or significant reduction in daily use) may be possible for patients on simple analgesia.

f) A gradual reduction or weaning over weeks to months is recommended for those using codeine and/or opioid containing analgesia.

g) In our experience, many of our more chronic migraine patients with MO/MOH may benefit from psychology support. This forms part of a multidisciplinary approach and is established practice at many specialist centres internationally.

h) Having withdrawn or significantly reduced the medication that is being overused, a full assessment of the underlying headache disorder should be undertaken.

i) The patient should then be given a plan to follow for acute treatment of the primary headache condition (Table 1), which is invariably migraine.

only available in specialist headache centres

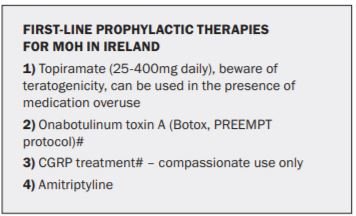

Long-term management of MO and MOH

If the patient still has frequent and disabling migraine, they should be assessed with a view to starting prophylactic or preventive treatment. (See Table 3) Topiramate, Botox and the novel CGRP may work in the presence of MO, but it is desirable that MO be addressed before starting any of these treatments. Topiramate should not be used in women of childbearing age due to its teratogenic side-effects. If MOH is present, many patients will experience a long-term reduction in headache frequency after medication overuse is stopped. Access to PREEMPT Botox and CGRP treatments are generally limited. Amitriptyline does not work in the presence of MO.

Patients with MO and MOH can have complex additional medical and psychosocial needs. Typically, it takes a number of weeks (or months) for a patient to get over the withdrawal of acute medication. However, it may take much longer, especially if there is longstanding MO or there is regular opiate or codeine use. Primary care physicians may be able to identify specific patients who may need additional support or benefit from psychology (or even psychiatry) input. In some patients who have ongoing issues with MO, addictive behaviour may be involved.

While it is generally recommended that NSAID use is also limited to four-to-six days a month (or one-to-two days a week), when MOH is present, naproxen may be used in certain circumstances for a longer period. It may be helpful to give a more prolonged continuous course of naproxen 250-500mg twice daily for two-to-six weeks with appropriate cover for gastritis. More prolonged use of naproxen in this manner does not appear to be associated with MO.

However, this practice should not be repeated frequently (multiple times every year) due to potential long-term side-effects of NSAIDs.

Over the years in clinical practice, patients often identify themselves that analgesia, in particular Solpadine, makes their headaches worse and they stop them themselves. Perhaps it is time for a national campaign again on MO and MOH.

Further information and support is available from the MAI, www.migraine.ie or from my website at www.marykearney.eu.

References available on request

Acknowledgments:

I wish to thank Dr Martin Ruttledge, Headache Neurologist, Beaumont Hospital, Dublin; and Ms Esther Tomkins, Advanced Clinical Nurse Specialist, Beaumont Hospital, for all the work they have done on this topic, which will be presented in full in the ICGP Quick Reference Guide on Non-migraine Headache Disorders: Diagnosis and management from a GP Perspective. This guide is due to be launched later in 2021.