Allergic rhinitis is a risk factor for asthma, with 10-to-40 per cent of people who have allergic rhinitis also having asthma symptoms

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease, usually characterised by chronic airway inflammation defined by the history of respiratory symptoms such as wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough that vary over time and in intensity, together with variable expiratory airflow limitation (GINA, 2020). Asthma affects over 380,000 people in Ireland; 7.1 per cent of Irish adults have asthma with 890,000 likely to experience it sometime in their lifetime. It is estimated that over 80 per cent of people with asthma have allergic rhinitis (AR).

AR is a risk factor for asthma – 10-to-40 per cent of people who have AR also have asthma. AR is more likely to develop initially with asthma developing later. Therefore, people with AR should be assessed for asthma due to the increased risk of developing asthma. Similarly, patients with persistent asthma should be assessed for AR.

Symptoms of AR

Typical symptoms of seasonal (hay fever) and perennial AR are:.

- Sneezing;

- Itchy, blocked, or runny nose;

- Red, itchy, or watery eyes;

- Itchy throat, inner ear, or mouth;

- Postnasal drip (a drip of mucus from the back of the nose into the throat);

- Headaches;

- Loss of concentration and generally feeling unwell;

- Reduced sensation of taste and smell

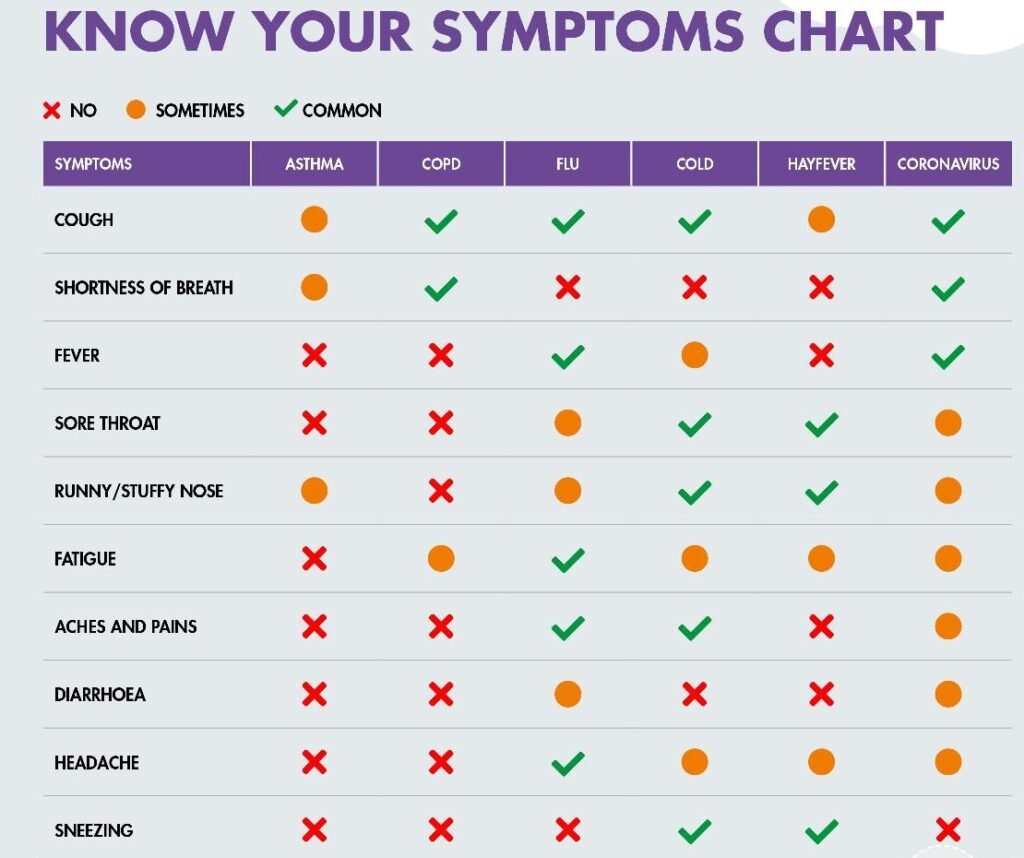

Patients may experience all or some of the above. Symptoms may be confused with symptoms of Covid-19. Figure 1 illustrates the differences between asthma, COPD, AR, Covid-19, the common cold, and flu.

Classification of AR

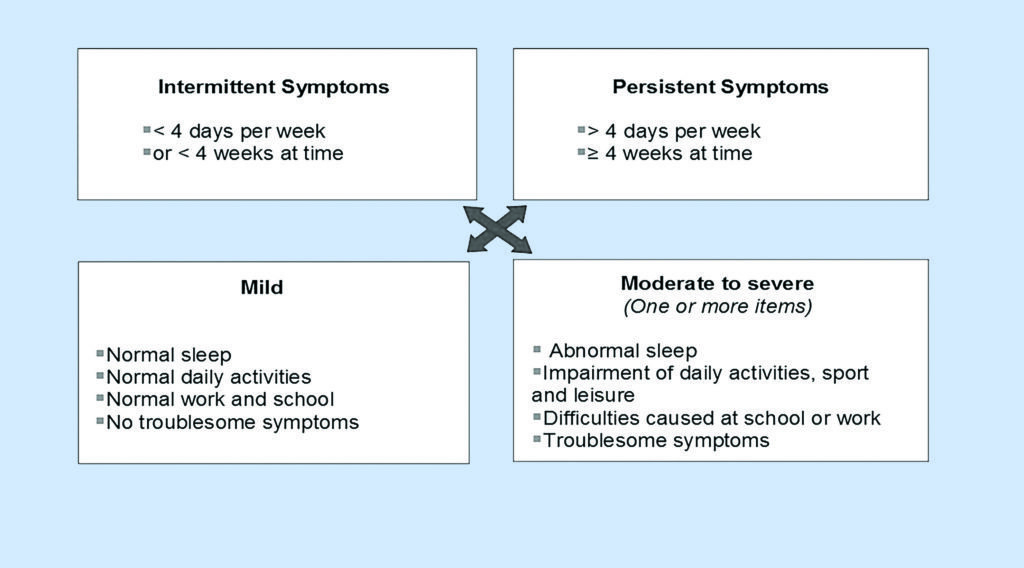

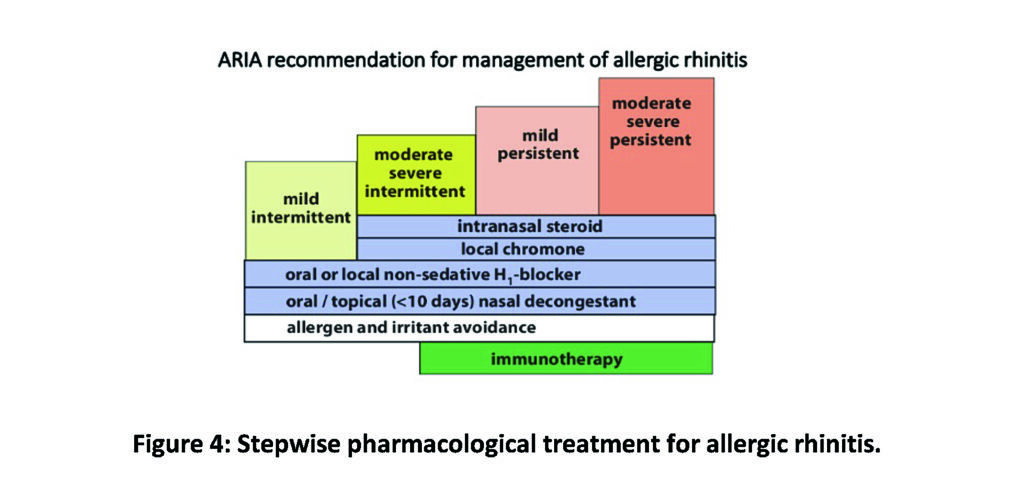

In 2019, the classification of ‘seasonal’ and ‘perennial’ rhinitis was changed to ‘intermittent’ and ‘perennial’ rhinitis by the Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) initiative, which develops internationally applicable guidelines for allergic respiratory diseases. Intermittent rhinitis is classed as occuring less than four days per week or for less than four weeks. Persistent rhinitis lasts more than four days and longer than four weeks. Both intermittent and persistent AR can be mild or moderate/severe (see Figure 2).

Presentation of the patient with AR

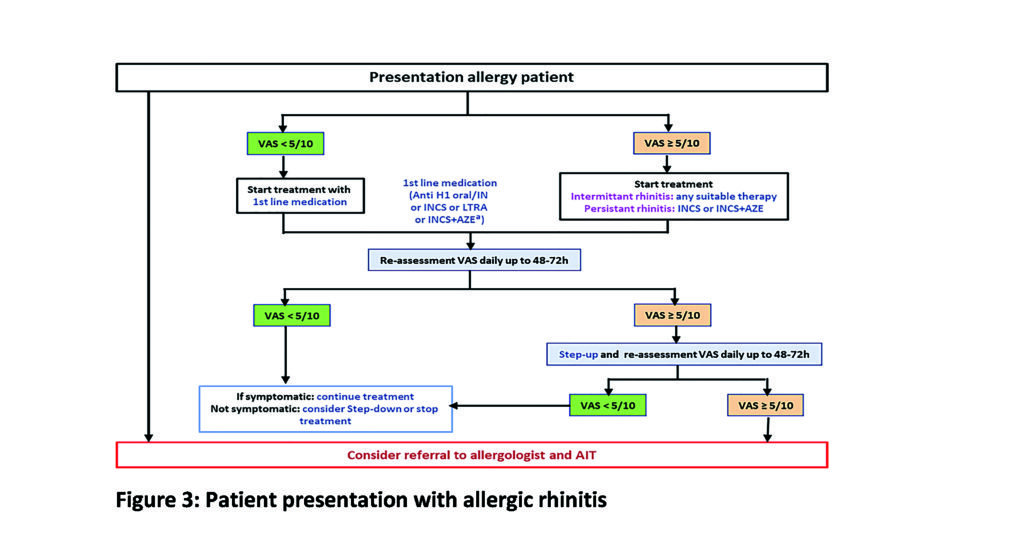

The early response usually occurs within minutes of exposure to the allergen resulting in an inflammatory response. Mast call degranulation occurs resulting in nasal congestion, an increase in nasal secretions and nasal airway resistance. Several neural peptides, sympathetic and parasympathetic fibres are involved. The late response usually occurs hours later resulting in cellular inflammation. Symptoms recur at this this stage especially nasal congestion. T-cells and mast cells also produce cytokines during the late response. See Figure 3.

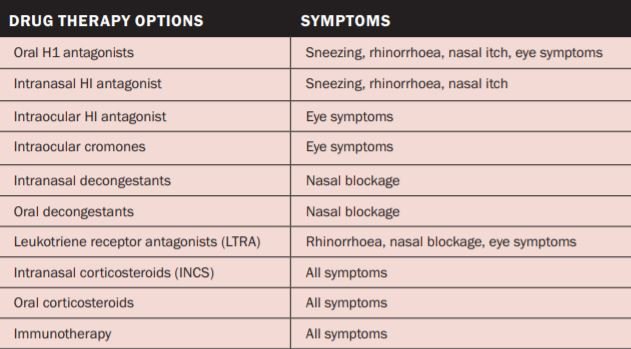

Pharmacological interventions (ARIA 2019)

There are several treatment options available to the patient and a combination of these options may be required for optimal relief of symptoms. These are outlined in Table 1. Saline douching/nasal irrigation should also be encouraged and is available either as a saline rinse or saline spray. Saline rinsing involves high volume at a low pressure, whereas saline spray is a low volume delivered at high pressure. The advantages of saline douching include:

- Direct cleansing;

- Removal of mucous and inflammatory mediators;

- Reduces bacterial burden;

- Reduces mucus thickness;

- Improves mucociliary function by increasing ciliary beat frequency.

Smoking cessation should be encouraged at every opportunity. Smoking increases the likelihood of chronic nasal symptoms and may be associated with the development of nasal polyposis. Passive smoking, environmental exposure, e-cigarettes, and vaping also increase the likelihood of chronic nasal symptoms and nasal polyposis. Mild intermittent AR treatment options include oral and nasal decongestants, which can be used as a rescue medication. These medications will reduce nasal congestion and should be used for no longer than seven days and should be avoided in pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Oral H1 antagonists block the physiological effects from mast cell derived histamine. Second generation antihistamines are preferred due to their less sedating effect and are available over the counter. Antihistamines are also available intranasally or intraocular. Intranasal corticosteroids (INCS) are the first-line treatment for moderate/severe intermittent and persistent AR. These medications are used once or twice daily to each nostril and good technique is essential. If the nasal cavity is very obstructed, a nasal spray may not be effective. Nasal drops may be more effective in this scenario. Nasal spray and nasal drop technique can be viewed on www.asthma.ie/about-asthma/resources/inhaler-technique-videos.

Efficacy of INCS is not improved when used with oral corticosteroids (OCS). Figure 4 provides a stepwise approach to the management of AR. Sub-lingual immunotherapy (SLIT)/allergen immunotherapy (AIT) is now recommended by GINA (2020) as a treatment option for patients with asthma who are sensitised and have AR. Immunotherapy is also recommended by ARIA (2019) for patients with AR who do not get an optimal response from oral H1 or INCS therapies. These medications are not available on the GMS and can be prescribed by GPs.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Lifestyle intervention

- Keep windows closed at night-time or when the pollen count is high.

- Monitor the pollen tracker on www.asthma.ie and minimise time spent outdoors when the pollen count is high.

- Apply Vaseline around nostrils when outdoors to trap pollen.

- Wear wraparound sunglasses to

- minimise levels of pollen irritating the eyes. Splash the eyes with cold water to help flush out pollen and soothe and cool the eyes.

- Shower, wash hair and change clothes if you have been outdoors for an extended period of time.

- Exercise in the morning rather than the evening when there are higher rates of pollen falling.

- Avoid drying clothes outdoors and shake clothes outside before bringing them inside – particularly bedclothes.

- Minimise contact with pets that have been outdoors and are likely to carry pollen.

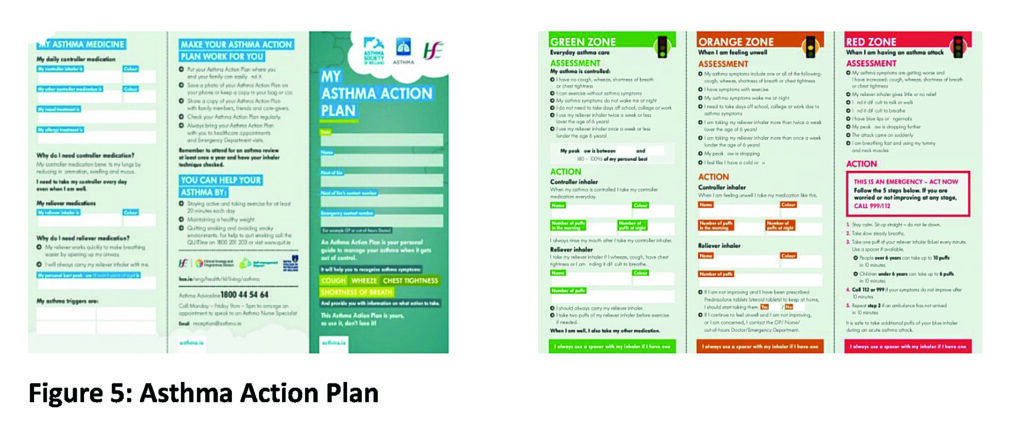

- Put an Asthma Action Plan in place (Figure 5).

- An Asthma Action Plan contains all the information a person with asthma needs to keep their condition in control. Every person with asthma should be offered a plan. It should be reviewed frequently and any time medication is changed. These can be downloaded for free from www.asthma.ie and should be filled out with the person’s healthcare professional.

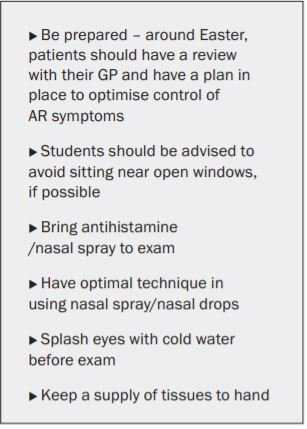

Exam time tips

Walker et al (2007) showed that students undertaking exams may drop a grade in their exam results because of AR as a result of symptoms, sedating medication, and poor sleep. Having AR under optimal control cannot be underestimated. Some tips to help with exam time are listed in Table 2.

Endonasal phototherapy

Endonasal phototherapy has an immunosuppressive effect by inhibiting allergen induced histamine released from mast cells. It also induces apoptosis in the T-lymphocytes and eosinophils. The procedure directs a combination of UVB, UVA and visible light into the nasal cavity. Endonasal phototherapy is generally well-tolerated and effective and is a treatment option when pharmacological treatment is insufficient or contraindicated.

Surgical intervention

It is considered that AR is a medical condition which requires medical intervention. However, if symptoms are unilateral; septal deviation, nasal polyps or tumour should be considered. Patients will still need to have an AR plan in place post-surgical intervention.

Special considerations in AR

Children under four years

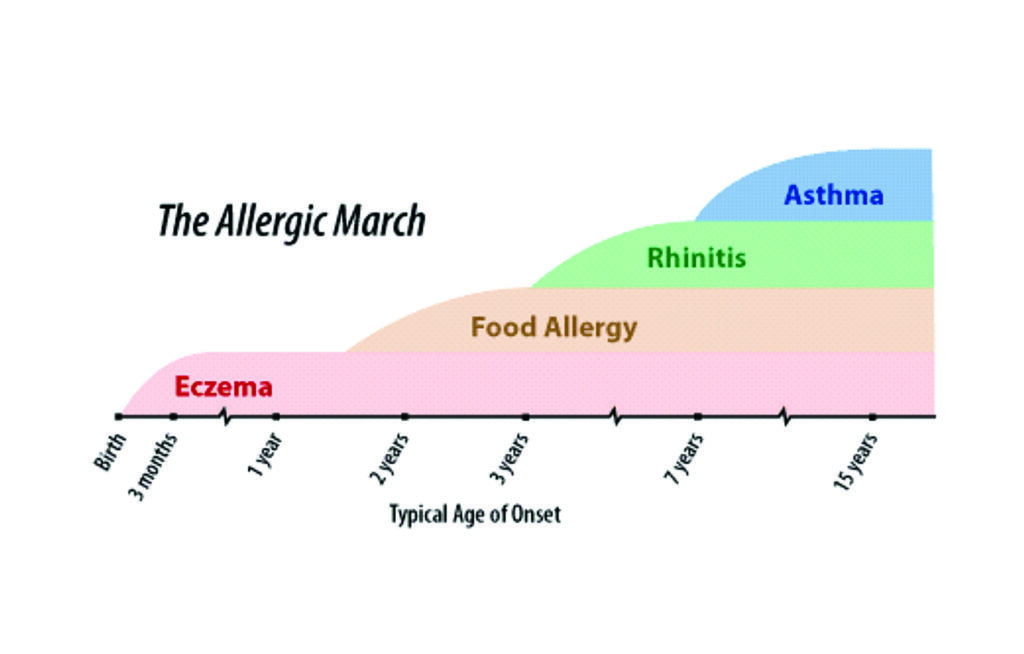

Figure 6 illustrates the typical age of onset of allergies in children. Outdoor allergens are unusual in children under two years of age. Type 2 sub-endotype IL4/IL-13 are associated with AR in children. IL-5 is associated with asthma. Treatment of children under four years should focus on allergen avoidance and saline spray. Cetirizine is the oral H1 antagonist of choice. Cetirizine is licensed from two years, but good safety is reported from six months of age. For moderate/severe persistent AR, intranasal corticosteroids such as fluticasone or mometasone should be considered first-line treatment.

Long-term follow-up studies suggest no growth retardation if used as a once-daily dose. Caution should be taken in children who are also using inhaled or topical corticosteroids for asthma or dermatitis. In children with resistant symptoms and those with co-existing asthma, leukotriene receptor antagonists should be considered. Parents should be educated in relation to possible side-effects of sleep disturbance and mood disorders.

Pregnancy

AR affects 20 per cent of pregnancies and women with pre-existing AR can experience an increase in symptoms. Medications should be avoided where possible and should only be used if benefits to the mother are greater than risk to the foetus. Medication should be avoided in the first trimester if possible. Topical administration of medication should be first-line where possible.

Conclusion

This article has explored the relationship between asthma and AR. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the management of AR have been discussed. Special considerations in children and pregnancy have been addressed. The impact of AR on health and well-being is significant, with many people experiencing impairment of daily activities, learning and cognitive function, as well as reduced productivity at work and school. Optimal control of symptoms through pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment regimes in combination with education, self-management, and empowerment are paramount to manage this distressing condition.

References available on request