An overview of the recent guidelines and literature regarding imaging and Covid-19

As of early October 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has infected more than 34 million people worldwide, resulting in over a million deaths. There are more than 36,000 confirmed cases in the Republic of Ireland alone with mortality close to 5 per cent. Imaging with chest radiography (CXR) and computed tomography (CT) plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of Covid-19 infection, both in the early stages to aid diagnosis, as well as in the later stages to assess severity and progression; and also to identify complications, such as pulmonary embolism.

The gold standard for diagnosing the disease is laboratory confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR analysis of nasopharyngeal swab specimens. This test is suboptimal for rapid patient triage as results are not available for several hours and it has low sensitivity in clinical practice (60-to-70 per cent -likely secondary to questionable sample quality, stage of infection or viral replication rate), which is insufficient to reliably exclude Covid-19.

Clinical presentation of Covid-19 is typically as an acute febrile lower respiratory tract infection; 15-to-20 per cent of patients develop severe disease. Primary imaging modalities used are CXR and/or CT thorax. Imaging thresholds are variable, partly dependent on local guidelines and available resources. In a consensus published in April, the Fleischner Society recommended imaging in i) patients with moderate to severe clinical features consistent with Covid-19 infection; ii) Covid-19 positive patients with worsening respiratory status; and iii) to triage patients with moderate to severe clinical features in resource-constrained environment with high pretest probability of the disease. Imaging is generally not recommended in those with mild clinical features without risk of disease progression.

CXR

CXR, especially in its portable form, is the most commonly used imaging modality for inpatient assessment of Covid-19 lung disease; it is easily available and has lower risk of cross-infection compared to CT imaging. CXR is useful in identifying suspicious lesions, ruling out obvious alternative diagnosis for similar clinical presentations such lobar bacterial pneumonia, pneumothorax and pleural effusion, as well as evaluating disease progression and recovery. However, CXR lacks sensitivity in the early stages of infection or mild disease, with no findings in nearly 70 per cent of cases that showed positive changes in accompanying CT thorax.

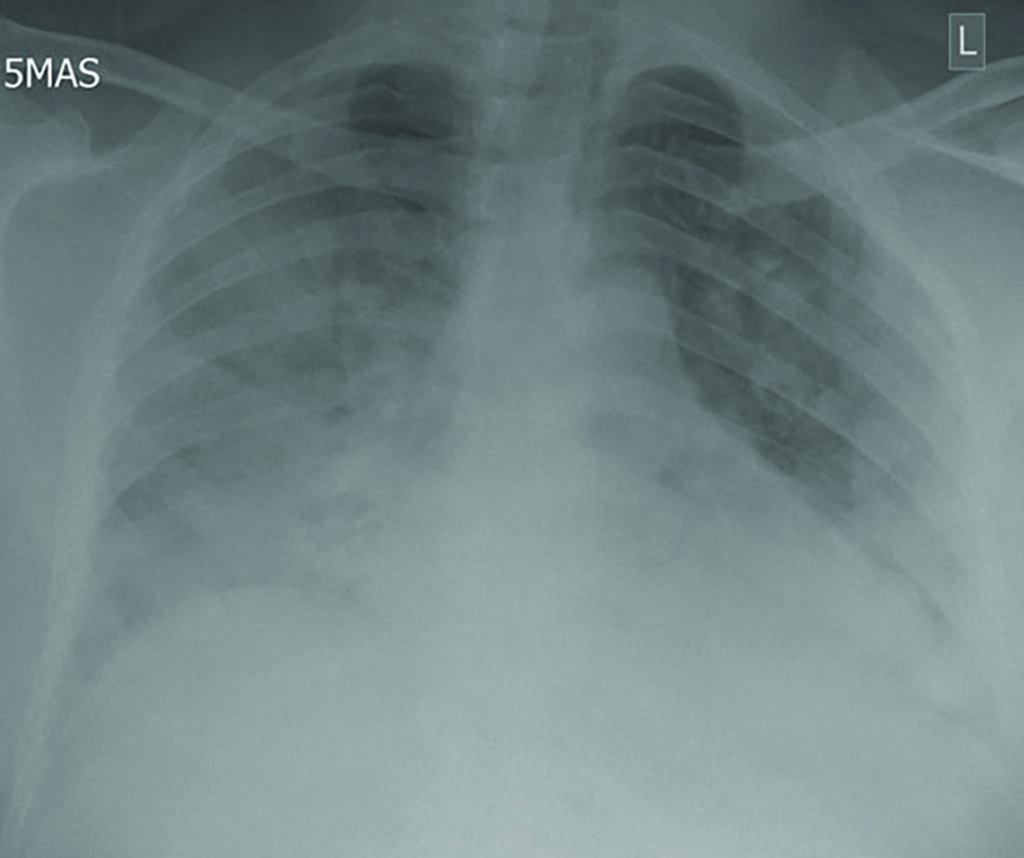

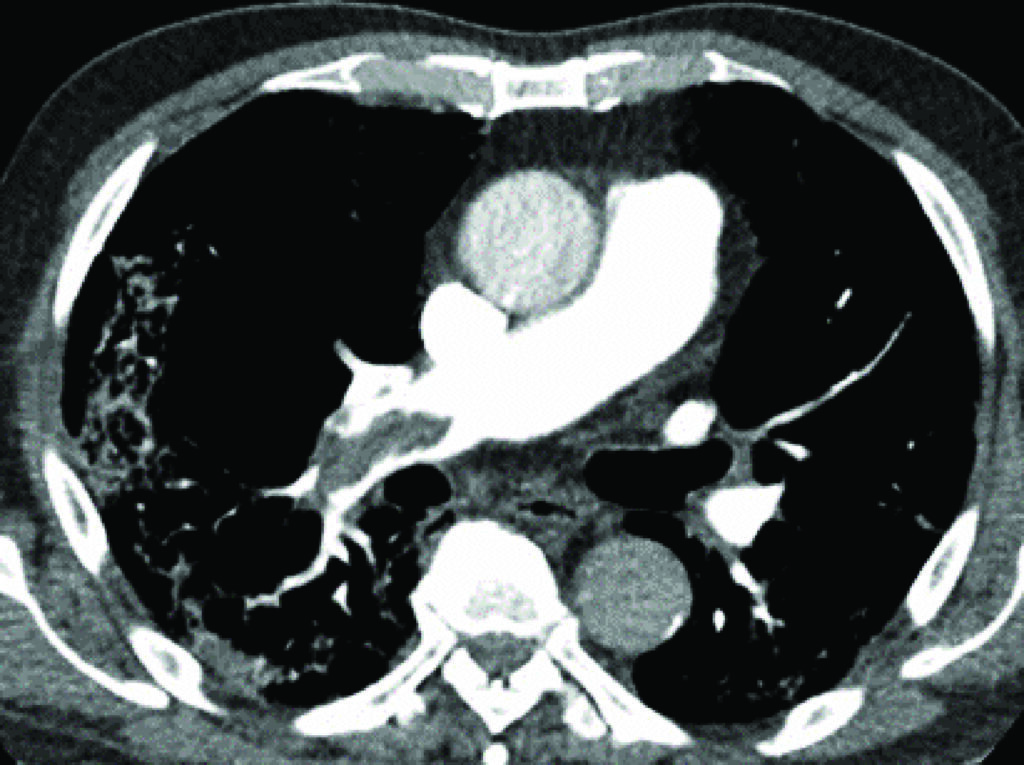

The typical findings on CXR are patchy diffuse asymmetric airspace opacities involving both lungs. Reticular and interstitial changes may also be present particularly later on in the disease. Helpful features in distinguishing Covid-19 from bacterial pneumonia is that the former is nearly always bilateral unlike typical bacterial pneumonia, which is often unilateral and unilobar. In addition, Covid-19 is usually multifocal and has a predilection for lower lobes and the periphery of the lungs. These changes often progress rapidly as the disease develops, deteriorating into diffuse consolidative or coalescent pattern, which usually peaks during the second week of presentation (Figure 1).

Templates for patient stratification based on CXR findings have been devised by organisations such as the British Society of Thoracic imaging expert reference group, which recommends assigning patients into one-of-four groups of classic/probable, indeterminate, normal and non-Covid-19 diagnosis. Qualitative and quantitative scoring method have also been developed, especially for the first group (classic/probable Covid-19), in order to assess severity. However, these guidelines have not been universally adapted.

CT thorax

Most of the literature on Covid-19 imaging has focused on CT thorax findings. Varying sensitivities and specificities have been reported by numerous studies; meta-analysis by Kim H et al reported pooled sensitivity and specific of 94 per cent and 37 per cent respectively. Positive predictive value of CT thorax is highly variable depending on disease prevalence, therefore in areas of low prevalence, many false positive cases would be picked up if CT were to be used as a screening tool. Wen Z et al estimated negative and positive predictive values of 92 per cent and 42 per cent respectively in areas of high disease prevalence, the latter suggests that CT would still not be particularly valuable for screening even in areas of high disease prevalence. While CT thorax findings could predate positive result on RT-PCR testing, its use as a primary screening tool is discouraged, partly due to the above reasons.

For CT imaging, low-dose non-contrast technique is recommended. CT findings may also be normal early in the course of the disease; Bernheim A et al found negative scans in more than 50 per cent of patients imaged within two days of symptom onset. However, this reduced significantly thereafter, with only 4 per cent of patients demonstrating normal scans when imaged six-to-12 days after symptom onset.

While some studies have reported that it is very unlikely for there to be no abnormalities in CT after the first few days of symptom onset, Adams HJA et al, conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis that revealed nearly 11 per cent of Covid-19 patients, almost all of who were symptomatic, did not have abnormal CT findings. On the other hand, Shi H et al, found abnormalities in CT imaging in patients even prior to symptom onset per cent. Adams HJA et al suggested that normal CT findings, even in symptomatic patients, should not be used to exclude diagnosis of Covid-19.

In practice, most Irish radiology departments use CXR as firstline chest imaging; CT is reserved for evaluation of severe disease and/or to investigate co-existing pathology such as pulmonary embolism or alternative diagnosis. CT also has significant utility in assessing patients with normal or indeterminate CXR or suspected initial false-negative RT-PCR albeit demonstrating concerning clinical features.

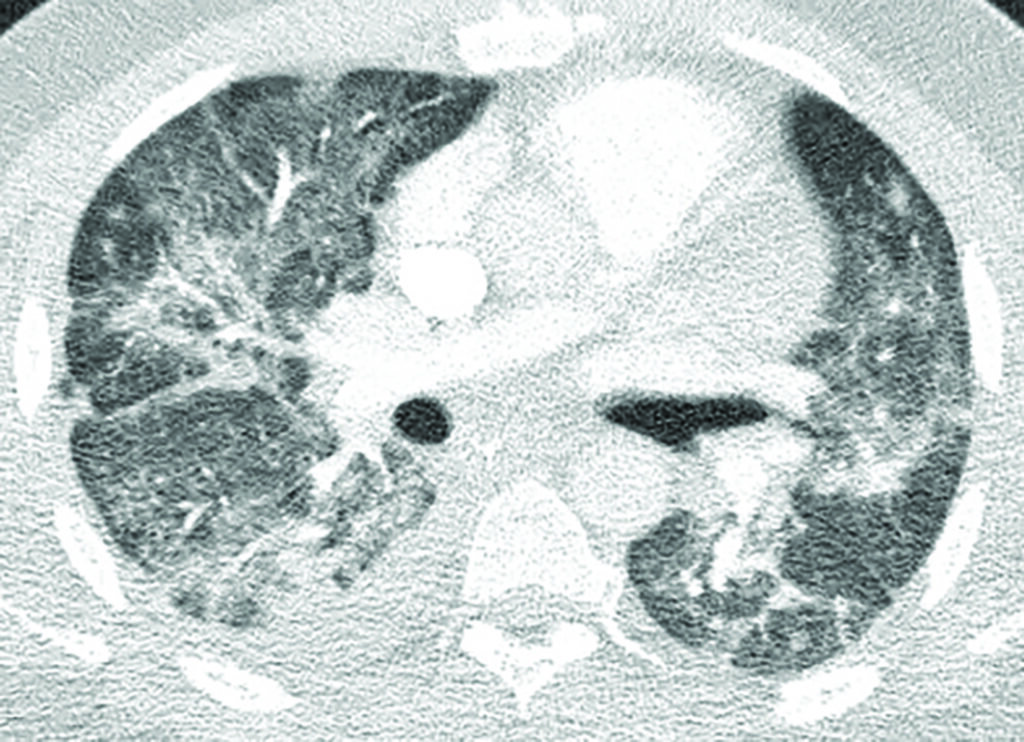

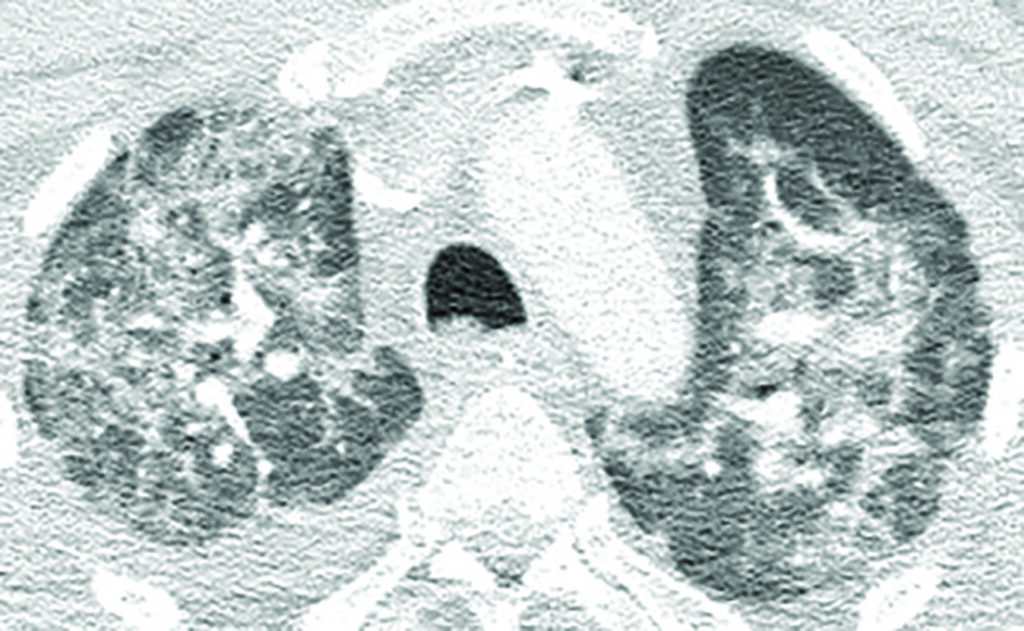

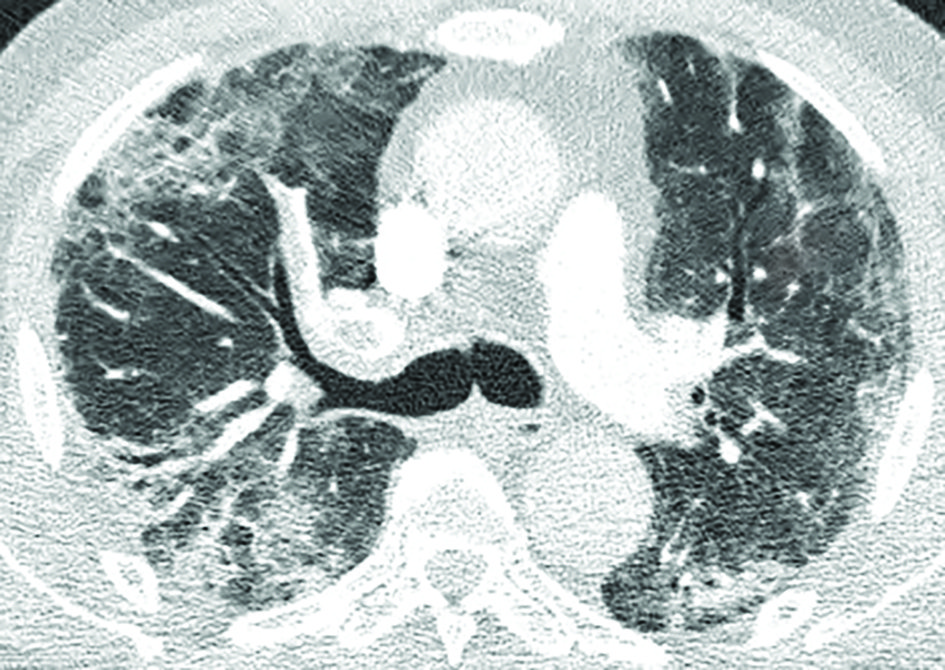

Common CT findings and stages of evolution of CT findings have been widely reported in the literature. Typically, Covid-19 presents with ground glass opacities (GGO), often with rounded morphology, with or without consolidation, in a peripheral, posterior and lower lung distribution. These may only be present focally unilaterally in the early stage (≤2 days). Initial findings overlap with those of other atypical pneumonias and are not specific to Covid-19. Suspicious findings in patients with previously abnormal lungs secondary to underlying co-morbidities could also lead to diagnostic uncertainties, especially if initial RT-PCR results are negative.

Both right and left lower lobe predilection have been noted by different studies. These findings could develop and become more extensive in the intermediate (three-to-five days) and late (six-to-12 days) stages, with progression to consolidation and bilateral lung involvement and interseptal thickening. GGO usually develops within four days after onset of symptoms and peaks at six-to-13 days, other usual findings in viral pneumonias such as thickening of bronchial wall and ‘tree-in-bud’ nodularity and bronchial mucus plugs are not frequently seen in Covid-19 patients. Pleural effusion and lymphadenopathy have been reported, but are uncommon; the former has been observed in our institution (Figure 1). Perilesional vascular thickening likely secondary to hyperemia in acute inflammatory response has also been reported.

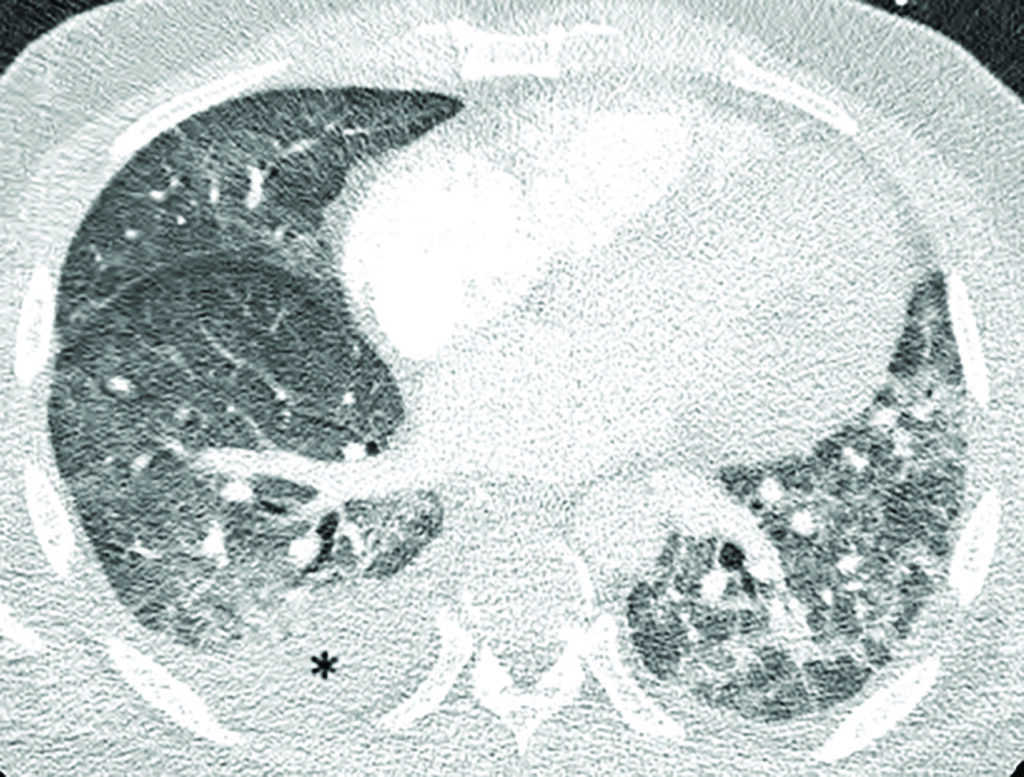

Features that correlate with clinical severity include greater lung involvement in first CT imaging, higher density of lesions and presence of architectural distortion with traction bronchiectasis in early imaging. In critically ill patients, consolidation predominates and appears more extensive compared to GGO. As patients improve, varying degrees of clearing have been reported in late stage CT (≥14 days) as previous findings decrease in size and attenuation value; fibrous band may appear. Abnormal findings, such as fibrotic streaks, could persist beyond one month. CT scoring methods have been devised by radiology departments to stratify patients’ risk; the extent of pulmonary involvement seen on CT correlated highly with clinical and laboratory parameters.

Up to 30 per cent of hospitalised patient develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) which appears as extensive diffuse bilateral consolidation predominantly in dependent lung areas. Covid-19 is associated with predisposition for thromboembolic disease, likely resulting from systemic inflammatory response and endothelial cell damage secondary to binding of SARS-CoV-2 to the ACE-2 receptor. Pulmonary embolism has been reported, especially in the setting of elevated d-dimers (Figure 2).

CT findings in Covid-19 are often classified into four categories: Typical, indeterminate, atypical appearance and negative for pneumonia. CT scoring systems, such as CO-RADS and COVID-RADS, have been proposed by international organisations, but these are not widely used at present.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic is an evolving situation, new cases are still being reported in the Republic of Ireland on a daily basis. It is important for healthcare workers and the general public to remain vigilant and exercise necessary precautions to control the spread of this virus. Continued research into identification of further specific imaging patterns and long-term sequelae of infection as well as development of national/international standardised guidelines in interpretation and reporting of images would help consolidate global knowledge and aid patient care in months to come.

References available on request